This write up is based on material from Steve Brunton's amazing course on youtube Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems. If you haven't seen this series, definitely go check it out, it gives you an intuitive sense for why you should care about dynamical systems, some practical examples and how to solve them.

I'm writing this is part because I forget things that I've learned easily and so this is just a means by which I'm hoping to both give myself a refresher and a resource to come back to later.

All the code for the graphs will be organized in intuitive subfolders. I'm running python 3.8 with numpy, scipy, and matplotlib installed.

So why should you care about dynamical systems? What a great question! Dynamical systems are all around us, you can see them in action in simple objects and phenomena in your everyday life. The motion of the bobble head on your desk? Dynamical system. The number of cases of Covid19? Dynamical system. The fuel consumption of your car? Dynamical system. Everytime, the rate of change of a variable in time is related to the quantity of the variable at that time you have a dynamical system. These systems give us a new tool for us to place in our modeling toolkits. Alright, lets get our hands dirty.

Wow, what a mouthful of a subtitle. Lets break it down with the example above. The First Order part comes from the fact that for the variable that we are concerned with

As an aside, lets take a look at some simplified notation. The first thing we're going to do is drop the

Alright, the last thing we'll do is drop represent

Lets try to come up with a solution for this equation. But what do we even mean by a solution? Basically we're just trying to figure out what this equation tells us about our variable

Okay, so at first glance it might look like our equation above doesn't really tell us anything about the variable

We have a few options here. We can either try to solve these types of equations by simply manipulating the variables we have, or we can try to approximate the solution the first method might give us. First, we're going investigate the method of manipulating the variables we have; this is what we call an Analytic Solution.

There are many ways to come up with an analytic solution. Let's look at one for now, and we'll look at three more methods later.

Let's look at our motivating example first. As we mentioned before this one is a first order ODE. The first thing we ask ourselves is "what functions do I know who's derivative is just a constant times itself." Well, we don't even really need an exact solution at this point, we just need some functions that sort of behave this way. A couple of function classes in our toolkit exhibit this cyclical behaviour when being differentiated. We have functions like

For

This seems like the function we want to be using with the addition that we'll make use of the chain rule. To understand why we won't use

Ok so lets play around with

Let's take a look at how this function's derivative behaves when we modify the exponent. If we add a factor

Take a hard look, do you see anything interesting? Yup! Its our solution. We take

If you feel like what you just watched was magic trick then you'd sort of be correct. All that we did is basically just guessed a solution that happened to work for this particular ODE.

There's one thing that we forgot to talk about. If you take a look at our solution, there's one thing missing. If we would have choosen

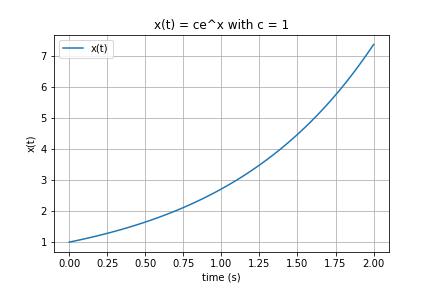

That's interesting, so it seems that for any constant

If you look closely, you'll notice that at time

This leads us to the general class of solutions to our problem:

Let's take a look at this from a bit of a different perspective. We're going to try to harness power of Taylor series to help us come up with a solution to our differential equation. For those, who haven't seen Taylor series before, I'll give you a brief introduction.

For functions that are continuous and infinitely differentiable, we can come up with an exact representations just using an infinite sum of polynomial terms, centering our approximation around a point

Below we have the taylor series for an arbitrary scalar function of one variable. Here

Let's get back to our original differential equation now. Since we don't know what our function is, let's assume that we can approximate it by a Taylor Series. We don't know the exact coefficients for it's polynomail terms but we can just try to write them out nonetheless.

Now lets compute

Using our differential equation we equate the two. Notice that both sides consist of the same powers of

Notice that we can simplify the denominators as factorials.

If we substitute this back into our equation for

Do you notice anything interesting about this? Yup, it's the Taylor Series for

Let's look at another method for solving differential equations. To demonstrate this method, let's first at a different problem than the ones we've been looking at so far. We're going to solve the problem below using method 1 first and then I'll show you a method using linear algebra that is equivalent.

This linear differential equation is one that uses the second order derivative of

Hooke's law describes the force acting on an object due to a spring that is attached to the object. This is expressed as

Since the only force acting on our object is the spring force, we can equate our two equations that we have. This gives us the following:

Lets assume that for now our mass is

Using our trusty exponential funcion we can try to find a solution to this system. Let's say that

At this point you might be able to guess what the value of

Then substitute in our guess for

If we were to graph

Now back to solving

At this point, you'll notice that two values of

So thats it right? We've got our two solutions and thats it right? We'll almost. This might starting hinting that if there are two solutions then there may be more. So lets take a detour for a moment and do a proof, thats going to show us that theres actually an infinite number of solutions to this problem. (Technically there are an infinite number of solutions, but if we are given initial conditions on our variables we will get one solution).

The general form of a homogeneous linear ODE is as follows (you should be able to find this on the wiki).

Here,

The following is what we want to show:

Say we have

Proof.

First rearrange the linear ODE so that the function

We will start working our way from the RHS towards the LHS to prove that this is true for

At this point we note that each of

Next we move the constants

We then collect like terms containing

But notice that the inside terms on each of the lines are just successive derivatives of

And so we realize that

Now, given that we already have two solutions, we can construct a more general solution based on our theorem.

For some constants

Ok, so we have a general solution now. But wait a minute, aren't we modeling a spring-mass systems? Where are the

If we expand our solution

Using the trigonometic propterties of

This leads to the following:

This leaves us with a nice little form for a general solution, although, its still a bit strange that there is a

In order to get a sense of this, lets introduce some initial values and solve for our constants

To come up with an equation for the velocity lets differemtiate the equation for the position of our mass.

If we plug in

With a bit of linear algebra or maybe just guessing you can figure out that the values of

Would you look at that! The imaginary term disapeared, and finally we have a position equation thats a simple oscillator. You can do the same thing to figure out the equation for the velocity of the mass. Just plug in the constants

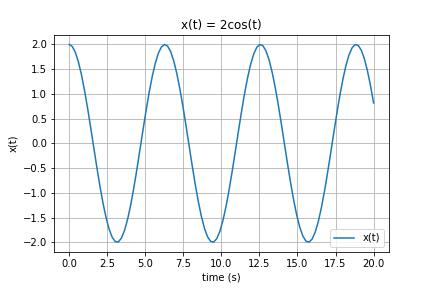

In summary, given a mass of $1$kg attached to a spring, with a spring coefficient

We can see this behaviour below in the position time graph. The mass oscillates forever since there is nothing to damp it's motion.

Ok so we have a way to solve ODEs in a couple ways now. But what happens when we want to solve a differential system with multiple variables and their derivaties? First I'll motivate a matrix representation for our problems and then we can solve a harder system using the matrix representation.

Let's look at this example for now:

Using our previous methods we can just guess the function for

Now we have a function for

Factoring

This equation is true in two cases. The first, which is not that interesting is when

Solving this using the quadratic formula we get the values of

I'll leave that to you as an exercise and instead we'll investigate an interesting idea. If you look closely at the equation we solved in terms of

Another way to look at this system is as a set of two equations which we can turn into a linear system and then solve. Rearranging our linear ODE equation we get the following two equations.

We can take the variable and it's first derivative and represent both of them at the same time as a stacked vector. We can then write our system as follows in the form

$ \frac{d}{dt}\begin{bmatrix} x\\ v \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1\\ -3 & -2 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x\\ v \end{bmatrix} $

You can verify that this represents our system faithfully. Now, let's try to figure out what the eigen values are for our matrix

$det[ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1\\ -3 & -2 \end{bmatrix} - \lambda I_2] = 0$

$det[ \begin{bmatrix} -\lambda & 1\\ -3 & -2 - \lambda \end{bmatrix} ] = 0$

This yeilds the characteristic function for the matrix

- Introduce matrix representation

- Show solution for decoupled system

- Show relatedness of general ODE system to its matrix representation

- Introduce eigen decomposition

- Show solution to general linear system problem

- Show different types of integrators: Forward Euler, Backward Euler, RK2, RK4, Symplectic Euler

- Analyze global and local errors of methods

- Show some real world examples